The Metropolitan Museum of Art currently has a great exhibition of 200 photographs from the 1840s to early 1990s called Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop. From the description:

The urge to modify camera images is as old as photography itself—only the methods have changed. Nearly every type of manipulation we now associate with digital photography was also part of the medium’s pre-digital repertoire: smoothing away wrinkles, slimming waistlines, adding people to a scene (or removing them)—even fabricating events that never took place.

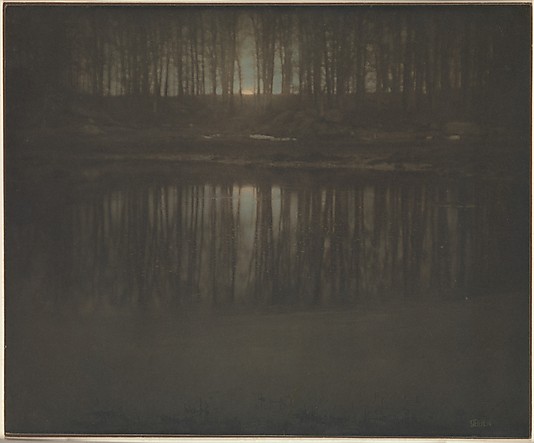

Here’s an example, with more at the bottom of this post:

The Pond – Moonrise (technique: multiple printing)

The exhibition is split up into different themes, and I was particularly interested in the section they call Artifice In the Name of Art:

The tradition of fine-art photography continued with Pictorialism, a movement that began in Europe in the 1880s and soon took hold in the United States. The Pictorialists sought to intensify photography’s expressive potential through the use of soft-focus lenses, textured printing papers, and processes that allowed the surface of the print to be modified by hand. In many cases, photographers composed their pictures from two or more negatives. Other artists, swept up in the currents of mysticism that captivated bohemian circles around the turn of the twentieth century, relied on staging and multiple exposure to reconcile the camera’s clear-eyed factuality with the ethereal realm of myths, dreams, and visions.

Soft-focus lenses… Textured printing papers… And we thought Instagram is a new idea. The outcome is the same — the difference is that the effects that we now get with the tap of a filter button used to take a very long time to do and was, in fact, part of a rebellion against the masses who took up photography as a hobby. The essay Pictorialism in America goes into more detail on this:

As an army of weekend “snapshooters” invaded the photographic realm, a small but persistent group of photographers staked their medium’s claim to membership among the fine arts. They rejected the point-and-shoot approach to photography and embraced labor-intensive processes such as gum bichromate printing, which involved hand-coating artist papers with homemade emulsions and pigments, or they made platinum prints, which yielded rich, tonally subtle images. Such photographs emphasized the role of the photographer as craftsman and countered the argument that photography was an entirely mechanical medium.

I find it fascinating how history repeats itself all jumbled up sometimes. As photography became popular in the 1880s, “real photographers” turned to labor-intensive manual methods for adding filters and effects to their photos to show that they are artists and craftspeople. Now that it’s easy to add those effects, the “real photographers” are rebelling again. Here’s Jaap Grolleman in Why I hate Instagram and why you should too:

I can understand people are trying to be cute but just because it looks ‘vintage’ and ‘antique’ it doesn’t mean a picture of your cat is cool. Pictures of clear-blue skies, light poles, bus stations, office chairs and even paving stones, they all look ‘aaamaazing’. Suddenly it’s all fashionable and presumingly ‘artsy’. I often see good photos being ruined by this ridiculous filter. There’s nothing artsy about it. Applying Instagram’s filters is just ‘clever-clever’, a bad attempt to fake authenticity.

And here is Rebecca Greenfield in Rich Kids of Instagram Epitomize Everything Wrong with Instagram:

The very basis of Instagram is not just to show off, but to feign talent we don’t have, starting with the filters themselves. The reason we associate the look with “cool” in the first place is that many of these pretty hazes originated from processes coveted either for their artistic or unique merits, as photographer and blogger Ming Thein explains: “Originally, these styles were either conscious artistic decisions, or the consequences of not enough money and using expired film. They were chosen precisely because they looked unique-either because it was a difficult thing to execute well (using tilt-shift lenses, for instance) or because nobody else did it (cross-processing),” he writes. Instagram, however, has made such techniques easy and available, taking away that original value.

If history is indeed a sign of things to come, the obvious question is: how will professional photographers rebel against Instagram’s easy filter manipulation? Will they go back to historical techniques? Invent some new, more difficult ways to manipulate photos? Or perhaps (gasp!) just take a photo and not retouch it at all? My money is on the rebellion spurring on some new innovation in art photography, and I look forward to seeing what comes out of it.

Anyway, now that the tangent is out of the way, below are some of my favorite photos from the exhibition. You can view the full collection here. These photos were all manipulated in some physical way — usually part of a very painstaking process.

Untitled (technique: combination printing)

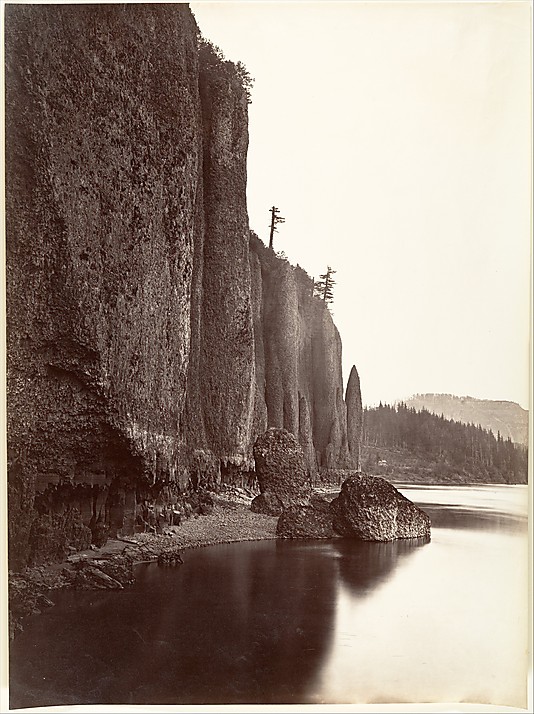

Cape Horn, Columbia River, Oregon (technique: wet plate negative process)

The Other Series (After Kertész) (technique: altering with bleach, dyes, and airbrush)

Étude de nuages, clair-obscur (technique: multiple printing)

17 Rio Pesaro, Venice (technique: cerulean wash)