Poorna Bell’s So Long, FOMO is making the rounds today:

At nearly every restaurant table I saw, there was at least one person (if not most) who spent most of their time taking photos or video to put on Facebook later, or searching for something on the internet, or playing games or just checking for texts. For more and more of us, technology is taking over, invading even our most personal and private of moments.

This idea that technology is turning us into antisocial monkeys is getting pretty old. Putting photos on Facebook helps you connect with others around the experience. Searching for something on the internet helps you move conversations forward (or change direction completely). All these activities are inherently social. Jason Feifer’s impassioned rejection of Sherry Turkle’s doom-and-gloom ideas provides a very good counterargument to all the fear-mongering:

Turkle imagines that any interaction with technology somehow negates all the time spent doing other things. She also imagines that we must devote ourselves in only one way to every task: At a dinner table, we are only serious and focused on conversation; at a memorial service, we are only mournful. That is not the way we live. It’s never been the way we live. And that’s the beauty of technology, which Turkle cannot see: We can use it for all purposes, to express joy and sadness, to have long conversations or send short texts. We made it. It is us.

It’s time for us to realise that we are evolving the way we communicate with each other, and that’s ok. I’m not saying we shouldn’t be mindful about how much time we spend staring at our phones, but we should recognize how much more social our devices are making us. Clive Thompson points this out in his book Smarter Than You Think:

What are the central biases of today’s digital tools? There are many, but I see three big ones that have a huge impact on our cognition. First, they allow for prodigious external memory: smartphones, hard drives, cameras, and sensors routinely record more information than any tool before them. We’re shifting from a stance of rarely recording our ideas and the events of our lives to doing it habitually. Second, today’s tools make it easier for us to find connections—between ideas, pictures, people, bits of news—that were previously invisible. Third, they encourage a superfluity of communication and publishing. This last feature has many surprising effects that are often ill understood.

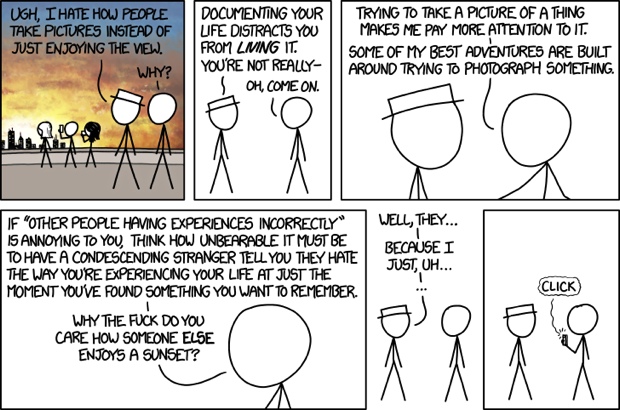

And we should also remember that it’s not up to us to tell people how to experience the moments that are important to them. As usual, XKCD says it best: